A Temporary Custodian

Richard West talks to Michael Wilson

Issue 34 Spring 2003

View Contents ▸

Richard West: Where were you born?

Michael Wilson: I was born in New York city, raised in California, went to university as an engineer and then went to Stanford Law School. Worked as a lawyer first for the government and then for a private law firm. During the Vietnam war I was working on military contracts, then I got into tax and international business law, about 1974 I came to London. The two year leave of absense became permanent, I've been over here ever since.

Richard West: What did your parents do?

Michael Wilson: My stepdad was a movie producer, came over in '52 and produced pictures all his life here.

Richard West: Subsequently you have become involved in film and photography. Do you chart your interests back to something around those times?

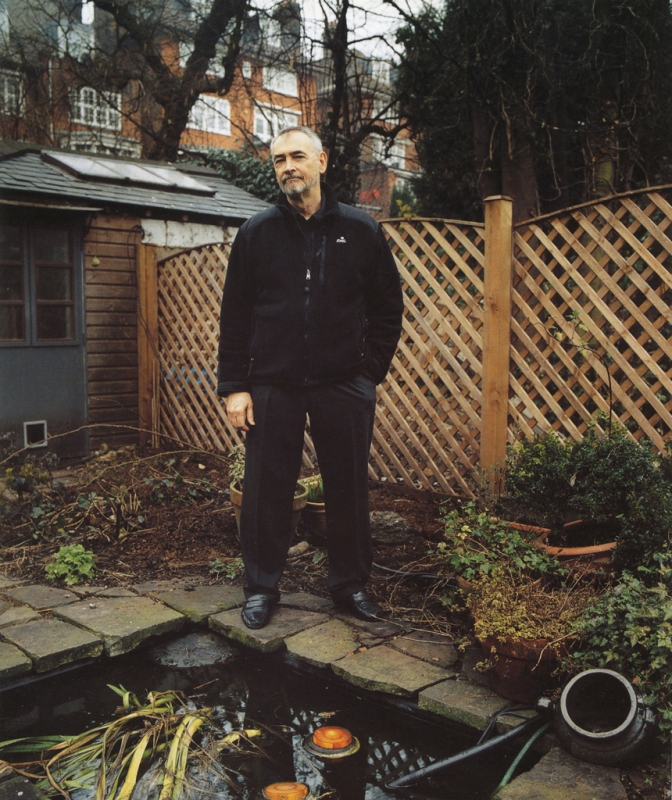

Michael Wilson: Well in the early days I began to collect things. I rapidly realised that you had to get a specialty and you had to get a focus. So I got into two areas, one was incunabula, books printed before 1500, and I put together a collection of those. I also collected prints and engravings from the French 1850s to the 1900s, and illustrated books from that period, from the United States, England and France. Those were the collections I was most interested in until I started collecting photography around 1978. Michael Wilson (portrait by Gareth McConnel)

Michael Wilson (portrait by Gareth McConnel)

Richard West: Did you start collecting photographs while you were still in the States?

Michael Wilson: No, I'd moved over here by then. I went back and forth a great deal. I had a friend who I'd gone to university with who was an assistant curator in photography and print at The Metropolitan Museum in New York. I used to go down and go to his house in Soho in New York. It was an interesting time down there and I would meet people like Ralph Gibson and Robert Mapplethorpe, they'd come round for dinner or they'd hang out and talk about photography. So I was in this milieu and exposed to it, but still hadn't quite made a connection with it.

Richard West: So were you already interested in photography or was it just this connection with your friend?

Michael Wilson: I think everyone's interested in photography and I'd always been a person who made photographs and had my own darkroom and did all that. I'd even taught photography as a practical thing to kids. When I was in Washington DC I used to run a classes for ghetto kids in photography. So I had an interest as an amateur maker not as a collector. About 1978 there was a sale at Sotheby's, I'd always gone to auctions, I'd go for auctions of the print stuff. My friend called me up and he said 'I've just looked at the catalogue for a sale and there are twelve things I'd like to purchase for The Metropolitan Museum, would you go and look at them for me.' I said 'I don't know anything about photography as far as evaluating it,' he said 'no, you collect works on paper, I just want a condition report.' It had about 350 lots in the sale, I went back and gave him a condition report and he gave me bids to execute. I went along to the sale; all his bids were too low. While I was sitting there I started buying - so he got nothing and I ended up with 60 lots out of the sale. That's when I started collecting.

Richard West: So it's the Metropolitan Museum that started you buying photography?

Michael Wilson: Yes. I'm going to give a talk out in California at the end of April about the relationship between the collector and the museum and I think it's interesting how, if you have the right kind of curators and the right kind of atmosphere in the museum, they can stimulate collectors, they can guide collectors; certainly that's been my experience. Then what happens is that as the collector gets more and more experienced he then can become helpful to the museum by becoming a trustee and things like that.

Richard West: The most obvious thing to come out of that is that you got the work and The Metropolitan couldn't afford to.

Michael Wilson: Sometimes museum people have that point of view, although the way it is right now they don't have any money to buy anything anyway, no matter what the price was they couldn't really afford it. I said 'forget about them, that's a very short sighted way of looking at it. They're banking all the stuff for you because they aren't going to last for ever. Collectors die, they have estate taxes to pay, eventually everything goes to the museums, the fact that it is delayed for 20 or 30 years is unimportant. If you have a good relationship with the collectors you can borrow it whenever you need it and you know where it is. They're just funding this thing for you and you'll get it later.' It's true that temporarily it's possible the collector is going to have this stuff but we're all just temporary custodians.

Richard West: Do you feel that your collections, in the past or presently, have had your character in them?

Michael Wilson: To some extent, the areas in which I collect reflect my character I suppose. I can't make a general statement about what I've tried to collect. I have uses for the collection and I guess I collect with that in mind and that is mostly didactic, educational, for exhibitions and stuff like that.

Richard West: You said that collections go to national museums, your collection started in America, you're now in Britain, has that become an issue?

Michael Wilson: You've highlighted a problem that I'd like to correct in England. That is that the English collections, and in France the French collections, are very parochial. One of the reasons I've brought my collection here and am teaching here - mostly art historians, that's who I'm trying to get to - is that this is about the only place you can see really important American work, really important French work, without leaving the country. It's unique in that respect.

Richard West: Is it important for Britain to maintain its national heritage?

Michael Wilson: I don't see that it's as important as the British do. That's a kind of political decision to be made. By concentrating on that and spending all their resources on that they end up with very parochial collections, art historians have to go to New York and Paris to see work by other practitioners in the history of photography. Think what the National Gallery would be like if the Impressionists were all English, it would be pretty poor. The fact is that art is an international idea and it moves around at different periods of time. It's the same with photography, by concentrating as they do on the national heritage for photography, they limit themselves terribly.

Richard West: You said art but photographs are seen as representing history. Maybe Roger Fenton's work has as much importance in representing a period of national history as it does in representing the art of photography.

Michael Wilson: I think those two things are pretty well bound up together and can't be unbound. You pick a good example, the idea that, let's say, Roger Fenton has to be kept in this country is a laudable one but there are enough copies of his work that you don't have to make the decision on every single picture. There are plenty of places that have copies of his work. When was the last time a Roger Fenton show was mounted in England? I can't tell you, maybe about the time he was living. The next Roger Fenton show that is coming to England is being mounted by three museums in the United States; The Metropolitan Museum, The National Gallery and The Getty are pooling their resources and putting together the definitive show of Fenton. So it takes the Americans, to do the definitive show of Fenton and that's because they appreciate it, they have good holdings in their collections, they can put a show together. So you have to ask yourself what's the point in having all the stuff here if that's the reality?

Richard West: How many of the pictures in your collection are of unknown authorship?

Michael Wilson: I have a large group of anonymous photographs because I try to collect image rather than necessarily artist. We could count the boxes, I think we'd see maybe forty boxes of early anonymous pictures. Much more than any museum would have by the way because they can't justify acquiring anonymous pictures.

Richard West: What's your relationship with scholars and art historians?

Michael Wilson: I was on a panel once where you had a lot of people from the photographic business. I was refered to as 'the end user' in this group. I had to point out that first of all I'm only the temporary holder and conduit, but if anyone's the end user, it's the public, they're the ones that are supposed to go and see those things, to look at them and respond to them. It's the job of the collector to preserve the stuff and the curator to select it and educate the public and give them an insight. There's a scholarly role in this and a critic's role. The critic's role comes at the very end and that's about whether the curator has done a good job, but I think the scholar's job is an interesting one. I think they can enhance the experience of pieces by giving you an insight into them. This can be additional historical knowledge that doesn't appear on the face of the object itself. They also become fairly elaborate in the social criticism and the symbols and the social structure of the day. They can get very far afield from what collectors or the general public are interested in knowing and that tends to be the area where there is some tension with other people.

Richard West: In comparison to the American market there seems to have been less appreciation of the potential value of photography in Britain.

Michael Wilson: There's hardly any market here, hardly anyone buys, even today. Almost everything is bought and exported.

Richard West: Do you have any idea why that is?

Michael Wilson: I think it's because there are no collectors, and there are no collectors because the government is the big collector, monopolises the whole area. There's no tradition of collecting, there's no tradition of giving either. Americans have a tradition of being involved in museums and local churches, this whole idea of tithing, even if you go beyond religious ideas it's very much engrained in American life so people believe in supporting and giving to hospitals and museums and all kinds of things. It's a different way of operating things. It creates collectors, they buy things museums can't buy, they donate them later.

Richard West: There were massive collectors of painting and sculpture, why don't you think that has translated to photography?

Michael Wilson: There are some, but photography is quite recent in collecting. The idea of the wealthy landed gentry collecting is an idea that started to fade even between the wars. But that means that those people who used to do the collecting aren't doing it so who's going to do the collecting? In fact it may be that among some people there is a negative aspect to collecting; you're competing with the government, there's a feeling that somehow it's associated with a time when there was social exploitation; that there may even be a negative aspect to being a collector.

Richard West: Why didn't you end up collecting contemporary photography as well?

Michael Wilson: Let's say I like the 19th century, I find it interesting. But there are two issues, one is that you have a limited amount of resources, you have an interest in an area and the area is challenging because you have to exercise connoisseurship. Now, how does that apply to contemporary photography, you're not going to collect anything that's unique, you're only going to collect things that are in big editions and are readily available in other places in museums or private collections. If you want to see a Mapplethorpe you're not going to have any trouble. It takes absolutely no connoisseurship, what are you going to say, that I have number one or number twenty seven, do I get a silver or platinum print? That's as far as you have to go. On the other hand you go to a 19th century piece, and there it is, it's being sold at auction, it's unlikely that anyone has seen it before, is this a good copy or not, what should it look like, if you've seen other copies of this piece is it better or worse than them? You have to know what you're doing or you make terrible blunders and I've made plenty of them but along the way I've learnt enough so that I can understand what I'm doing. Most of the pictures I have you can't get anywhere else and if you can I try to have the best examples because over the 150 years that they have been around there are very few that are as good as they can be. I want to show people Talbots the way they were supposed to look.

Richard West: Is there is a diminishing amount of material coming on the market?

Michael Wilson: Well that's what the dealers tell me. But I keep on getting as much as I can afford because the prices keep going up and I keep on getting good pieces. I'm in a very small market, I would say there are 100 people and maybe 50 or 60 institutions. That's the market, a tiny market but very competitive.

Richard West: You must know a lot of the other collectors, is there much exchange of information, is it a fraternal grouping or not particularly?

Michael Wilson: After the last sale we have a party. Everyone who comes to London, the dealers, collectors, who run the auction galleries, everyone comes here and has a drink. It used to be - it isn't any more because we've gone to a higher level - but people used to go into my office and they'd borrow a knife and cut albums up and divide them up between dealers. So it used to be that wild and wooly but it's got a little more sophisticated. So I meet everyone who's fairly serious in the business, we all socialise, I'm happy to share any information with people and have always felt that people are fairly open with me.

Richard West: You're giving classes about the work, could you say a little about that?

Michael Wilson: I've done the course before at the University of California about three years ago. I had seventeen PhD students and three museum curators. I'm doing a similar thing with the Royal College of Art starting this February. We'll cover the history of photography from the beginning to the Second World War in ten weeks. Five of them are practicing photographers on their MA, the rest are art historians working at museums and auction houses.

Richard West: Could you say what you want people to take away from the experience of seeing these pictures?

Michael Wilson: I feel that there is a lot of theory and interpretation in art history classes but there is probably less of an appreciation for the aesthetic aspects of photography and looking at a photograph as an object. So I'm just trying to expose people to that idea and by going through the history of photography and looking at good examples people get an understanding of it, so when they get around to curating shows they will be more attuned to this aspect of things as well as the interpretative ones.

Other articles by Richard West:

Source Photo: Do we need Photography Galleries? [Blog Post] ▸

Source Photo: The New Photo Galleries: A US Perspective [Blog Post] ▸

Source Photo: List Mania: 2011 Photobook Roundup [Blog Post] ▸

Source Photo: Is There a Crisis in Art Book Publishing? [Blog Post] ▸

Source Photo: Charlotte Cotton Resigns Media Museum [Blog Post] ▸

Issue 52: Teenage Girls at the Edges of Cities at Night... [Feature] ▸