Can Seeing be an Art Really?

Kendall Walton and Patrick Maynard are both philosphers who have written extensively about photography including Walton's 1984 essay, 'Transparent Pictures: On The Nature of Photographic Realism' and Maynard's book of 'The Engine of Visualization' (2000). Both philosophers spoke to Richard West about what their subject could contribute to our understanding of photography.

Issue 53 Winter 2007

View Contents ▸

Richard West: When were your first encounters with photography?

Kendall Walton: I don't consider myself a photographer. I own a camera and once in a while take pictures, and I have always enjoyed looking at photographs of different kinds for aesthetic pleasure, but also for lots of other reasons as well. I'm not sure that you can separate the aesthetic pleasure from other kinds of interests.

Richard West: Do you remember when you first started to take photography seriously as a philosophical subject?

Kendall Walton: I was interested in philosophical problems to do with the visual arts for a long time but I considered photographs and paintings alongside one another. Then at some point I decided to figure out what was distinctive and special about photographs and why some people think of them as being much more realistic than other pictures.

Richard West: Patrick, when did you start to think about photographs philosophically?

Patrick Maynard: I started with an extremely cheap camera made by Agfa which was good because I looked through a piece of glass that had no correlation to the lens, and had to calculate shutter-speed, distance, aperture in order to take pictures. As far as looking at photographs, I think mostly it's been books and magazines that have affected me, and in magazines it tended to be news photographs that had a visual impact on me. The interest in photography as a philosophical subject I think happened at the same time as Ken. I was invited to give a talk at a conference on photography. I was trying to write something on representation and I said 'Sure, I can just work this out of my stuff', but when I started looking for philosophical literature there wasn't any on photography, so I had an awful time. In fact some years later I put together a bibliography and you could fit it on one piece of paper. Julia Margaret Cameron, King Arthur, c 1874 Royal Photographic Society Collection. The image was made to illustrate Alfred Lord Tennyson's Arthurian epic Idylls of the King, first published in 1859. The model for King Arthur is William Warder, a porter at Yarmouth ferry pier.

Julia Margaret Cameron, King Arthur, c 1874 Royal Photographic Society Collection. The image was made to illustrate Alfred Lord Tennyson's Arthurian epic Idylls of the King, first published in 1859. The model for King Arthur is William Warder, a porter at Yarmouth ferry pier.

Richard West: If you wanted to know about photography what would be the questions that the philosopher would be best equipped to ask?

Kendall Walton: I don't think philosophy is so independent or distinct from other fields. But what in particular? Well, I think there's a lot more to be said about photographs and responses to them as compared to other types of pictures. That's an empirical matter but philosophers can contribute by keeping things straight and making the distinctions that need to be made. For instance, the process of photography is often said to be mechanical or automatic in a way which painting is not. But there are two different sides to that. One is the fact that there seems to be some kind of mechanical causal relation between objects in front of the camera and the resulting picture, which is different from the causal relationship when you have a painter involved. But there's another sense in which photography is automatic, and that is the fact that when you make a photograph it happens all at once by doing one thing. You may spend lots of time looking at the scene and doing your settings and so forth, but all you have to do is click the shutter. You can't do that with painting or drawing, every little bit has to be done separately. One consequence of this is that in photographs there are often accidents that would not be accidents in a painting. This is quite different from the type of automatic-ness which relates the object, the scene, to the photograph itself.

Richard West: Patrick, if you were going to ask a philosopher to write or talk about photography what would they bring to the subject?

Patrick Maynard: I see it in two ways. First is a head clearing effort - desperately needed in this case - and second is to talk about individual works with the results of the head clearing and see what happens. The head clearing is, in a way, negative. For example people have got woefully confused about the issue of realism and the mechanical. Photography is a technology - part of it with artistic application but most of it not - and it's one of a family of technologies which is rapidly changing. The issue now is digitalisation and everyone talks about authenticity and truth in news photographs. What they don't say is that the Galileo Jupiter probe was full of digitalisation: used 'false colour', as does medical imagery. There's a strange suspicion about the use of photography in certain contexts, while it just doesn't occur to people to ask, 'You mean I'm looking at the moons of Jupiter in false colour? Why are you making false colour?' Guess why, we are changing colours to allow us to see them better. Notice too, how, despite its digitalisation, the popular camera market is still sticking with that arbitrary 3x2 format, which was accidental, because the guy who was developing the small camera had a lot of 35mm cinema-film stock around, so he built the miniature camera around it, and it became an arbitrary standard, like the 'qwerty' keyboard still in the age of word-processors.

Richard West: Ken, when you started writing Transparent Pictures what was your initial project?

Kendall Walton: I argued that there is a certain sense in which photography is especially realistic, namely that when you see a photograph of something you're actually seeing the thing, and that's not true of a painting. Photographers in general seem to resist this. I think partly because they think that if we understand photography as an aid to vision - like mirrors and telescopes - that will denigrate the contribution of the photographer and make it seem as though the photographer is nothing but an overseer of the mechanical process. But on my view you might think of the photographer as someone who is showing viewers things by making photographs of them. When you show someone something you point to it or say 'Look over here'. Whoever is doing the showing has lots of control over what people see and over what people notice, and this can be a very expressive kind of act. This is the sort of thing which, traditionally, many people have thought is important to art. Some have thought this expressiveness isn't present in photography if photography has some sort of special realism, a special connection with the world. I was trying to show that these two things are not in tension: the mechanicalness that is crucial to transparency and the artistic or expressive function of the person who makes the picture.

Richard West: Patrick do you have a similar discussion about the expressive potential of photography as an artistic medium?

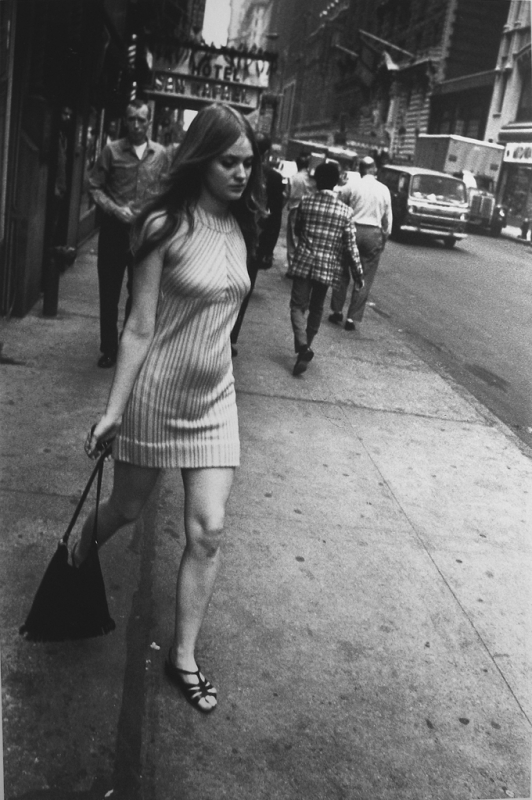

Patrick Maynard: Where Ken and I would differ is partly linguistically and partly about what bothers artists. I never use the word 'transparent' for the following reason: when we look through transparent things like eye-glasses, windows, we don't look at them. What the artist needs to be told is that there's no conflict between photographs which aid vision and photographs which you look at, as things - because most photographers, like other artists, want to have made an object. Some photographers would even think, as Alfred Hitchcock did, that they are using the subject and the light and the mechanism to make a thing, and that that thing is a photograph. So photographers are likely to suppose, when they encounter the word 'transparent', that attention is being given to one of the factors that they have used to make the photograph, rather than to the photographic work itself. Untitled by Garry Winogrand, from The Man in the Crowd: The Uneasy Streets of Garry Winogrand.

Untitled by Garry Winogrand, from The Man in the Crowd: The Uneasy Streets of Garry Winogrand.

There's a range of what I would call the 'nay-sayers' of photography as an art. The early ones had aesthetic worries, notably to do with its ability to produce painterly qualities that they required at the time. But through history the main worry has been whether photos are sufficiently due to the photographer to be expressive of a mind. That's the way Lady Eastlake put it in the 1850s - that our problem is to 'decide how far the sun may be considered an artist'. In those days they didn't just ask, 'How much of it is due to the artist and how much to mechanism and subject?' They also talked about something that current discussions tend to exclude: light.

There are interesting things about a more recent nay-sayer like Roger Scruton. He is the only one that's denied that photography is a form - much less an art - of representation. He says, because it allows an actual perception of a thing or situation, a photo can't at the same time represent it. The answer to this should be clear from the movies. In cinema you get the indirect perception of things, but you also get depiction of them, or of other things. The stuff in the background might represent, depict, stone, but what you are actually seeing is Styrofoam. No problem, you get both together, representation (of stone), indirect perception (of Styrofoam). Indeed, as Ken has pointed out, one of the interesting illusions in cinema concerns what it is we're indirectly, but actually, seeing. (Michael Roemer reminds us how people delight in watching an actor breathe when the character's supposed to be dead. Or, as a guy in a photo store pointed out to me, in films like Blow Up we see people shooting lots of pictures but the rewind crank wasn't turning, because, of course, the actual camera was empty.) Anyway, in my view, indirectly perceiving is completely consistent with other artistic functions. Photographs are depictions, and beyond that, works of pictorial representation - that is they represent things that they don't depict - and that interacts interestingly with the ability they give us to see. Saying that 'because it does one thing, it can't do the other', is usually missing the point about the arts. The arts are fun and artists are what they are because they like to get things to interact - peacefully or not - art's a business of relationships. Take Julia Margaret Cameron's photograph of King Arthur. A lot of those nineteenth century photos are just awful, the way they have somebody acting. Her pictures should be terrible, with all the Victorian props, poses, expressions. But, when you look at it, the actor and the role sometimes don't fall apart, though you get both - one indirectly seen, the other only represented. She has a formal ability so powerful that her photos are often like movies, I think.

Richard West: Ken, what consequence could your idea of transparency have for the way people understood the medium?

Kendall Walton: Well, it's arguable that most people who are not philosophers pretty much understand photography in the way that I describe it, without articulating it and without quite knowing why. I am trying to explain the reactions that ordinary people have toward photography. One example is that most ordinary people think that photographs, as opposed to paintings, have much more potential for invading privacy. If a painter is looking with binoculars at a celebrity on a yacht and draws something, that is not as much an invasion of privacy as if they used a camera with a telescopic lens. Whereas philosophers who insist that there is no particular difference between painting and photography will say that people are just irrational when they think of photographs and paintings as they actually do.

Patrick Maynard: Two other cases beside the paparazzi: one is court room photography, second, was the debate about the Kennedy assassination - they wouldn't publish photographs of his head but they did publish drawings of entry and exit wounds. Because in the case of the photograph you would actually be seeing the damaged head. In a drawing you may be getting more information, but it still won't have the psychological impact of the photograph.

Richard West: The second part of our conversation has been about the possibilities for artistic expression through photography, what are the consequences of transparency for that?

Patrick Maynard: Seinfeld claimed that stand-up comics have the toughest stage jobs because they have to be so much in the moment. Nancy Newhall had held that photography is the hardest of the visual arts, for similar reasons: that you must find, in an actual, fleeting, visual situation, something that will work, rather than making the situation up yourself. A Garry Winogrand might provide a simple example. In one of his photographs, of a woman walking along a city street, he aligned the vertical axis with her body. He tipped his camera and let the street perspective go. The result is that she appears like a goddess. There was a gravitational frame, also a perspective frame, which don't match the framing of the picture. That's one simple way in which you get the photo being, as Winogrand said, 'different from the reality'. You can see it's crooked but don't adjust it - shouldn't wish to - even though the whole perspective of the street has changed. Note this isn't something you could do with the real scene by tilting your head. Thus we get something that many photographers insist on: people experiencing seeing things differently, by means of the photograph. That is, not only seeing differently but seeing things photographically differently. What you experience in this photograph isn't exactly something that the photograph gets you to see on the street - that is, it's not a matter of 'capturing' what people were already experiencing (though that's important in photography, too). So, we have a distinct form of experiencing sight, due to photography, but it is actual, indirect seeing. In a similar way, the photo's stillness affects perception. It allows us - as indicated by the corniest old use of the term 'aesthetic' - to contemplate something that we couldn't otherwise.

Other articles by Richard West:

Source Photo: Do we need Photography Galleries? [Blog Post] ▸

Source Photo: The New Photo Galleries: A US Perspective [Blog Post] ▸

Source Photo: List Mania: 2011 Photobook Roundup [Blog Post] ▸

Source Photo: Is There a Crisis in Art Book Publishing? [Blog Post] ▸

Source Photo: Charlotte Cotton Resigns Media Museum [Blog Post] ▸

Issue 52: Teenage Girls at the Edges of Cities at Night... [Feature] ▸

Other articles on photography from the 'Multi-Genre' category ▸