|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CONTEMPORARY APPROACHES TO PHOTOGRAPHY:

PORTRAITURE & THE HUMAN FORM

by Jesse Alexander

Portraiture, in its various forms, is one of the most established genres in every different discipline of art. We take photographic portraits for granted, taking them has become so in-grained and almost ritualistic within our lives. Over a lifetime, we will have our portrait taken regularly, especially at significant moments such as birthdays, after graduation from college, with a first car perhaps, and certainly on a wedding day. But what do we really mean by the term 'portraiture'?

In terms of painting, the word might conjure up images of oil paintings of aristocrats and historical figures gathering dust in public galleries and country houses. The artists commissioned to paint such works would firstly be attempting to record a (flattering) likeness of their patrons, but also somehow represent aspects of their character, their occupation or their personal ideology. Certain conventions have evolved within portraiture, such as subjects sitting or standing still; smiling or appearing deep in thought; subjects addressing the artist/viewer directly or looking ponderingly into the distance. These conventions still dominate even contemporary photographic art, although the genre continues to progress, in terms of style, technique and the photographer's personal approach to their subject.

In the exotic photographic work of Fay Claridge, classical painting is referenced by using the sort of painted landscape backdrops that might be added in to portraits of aristocrats. Claridge's subjects are often masked in one form or another, which in a way challenges the idea of portraiture itself. In her series Only a stranger can bring good luck, only a known man can hang, Claridge photographed a group of Bedfordshire Morris dancers. In this series the colourful paraphernalia adorned by the sitters dominate the portraits, yet subtly hint towards the dancers' lives outside of their eccentric costumes.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Louise Maher's photographs of Catholic priests, Fathers take the viewer into her sitters' private homes. By shooting at a distance from her subjects, she is able incorporate the various domestic objects that furnish the priests' homes, publically exposing aspects of their individuality that is usually kept behind the cover of their uniforms and their church. Next to the images, Maher includes the sitters' testimonies of how they came into the priesthood, which accompany the open narratives within the photographs.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Similar to Maher, Elina Jokipii uses the written memories of women recalling their experiences of childbirth as they are photographed re-enacting their various birthing positions. The use of the subject's own words can also allow more of their personality or an aspect of their life to come across, rather than simply relying on their photographic image alone to do the talking. In a sense, it allows the subject to make his or her own contribution to the process of portrait making, which we might understandably assume to be the photographer's responsibility alone

|

|

|

|

|

|

Using a prescribed backdrop rather than a particular or defined group of people can lead to a more unexpected series of work, such as in Adrian Arbib's collection of portraits taken on Port Meadow. In this work, Arbib found that returning to the common land near Oxford with his camera and photographing whoever happened to be there revealed much about how the public space was shared. The work is as much a portrait of the meadow as it is a collection of portraits of individual people.

|

|

|

|

|

|

One of the most common conventions of portraiture is that the subject is looking at the viewer or, at the very least, aware that they are being observed and have give their consent to being photographed. This very idea is challenged in Ben Graville's series In and out of the Old Bailey. While working for a press agency, Graville photographed through the windows of prison vans while waiting to take remand prisoners into court. The intriguing snap-shots reveal a very secretive and forbidding space inside the vans, dominated by the prisoners who betray a variety of emotions and personalities. Due to the unpredictability of this process, Graville's images are chaotic and at times abstract. Graville doesn't even fill the frame with the subjects, which only adds to the sense of stress and false bravado of the prisoners who are facing up to the camera.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ben Graville's series also highlights how the conventional idea of representing the face alone within a portrait can be extended to recording other parts or aspects of the body. Wiebke Leister photographed children being tickled with unpredictability strangely similar to that of Graville. In her series, Neck Over Head the children photographed at high speed show, with their bodies as well as their facial expressions, a variety of postures and contortions that seem in some ways peculiar. Leister's series is unsettling to viewers as it is difficult to decide whether the children are in a state of hysteric laughter, or in fact crying out in pain. This work reminds us of how the camera is able to freeze a split-second moment with amazing visual clarity, but it also shows us that the photograph has limitations in that the true, original content of the moment depicted can easily be taken out of context to tell a different story.

|

|

|

|

|

|

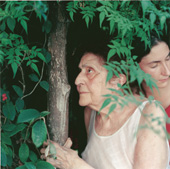

As we can see in Leister's work, the photographic image can record the intimacy of human expressions and emotions with remarkable precision. In Claire Waffel's series of staged portraits Close Family, she explores the inter-relationship between herself and her grandmother. The photographs are poetic rather than descriptive and have ambiguous, open narratives. A similar sort of idea is explored in the digitally manipulated work of Eva Stenram.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Close Family

by Claire Waffel |

|

|

|

|

In recent years, artists have accepted the limitations of the photographic image to convey a sense of an individual - in terms of their personality, their background and so on - and the somewhat superficial way in which the camera simply mechanically records a person's image. Partly as a result of this, there has emerged a fashion for expressionless, 'deadpan' portraits in photographic art. A key figure in this development is the German photographer Thomas Ruff, whose use of the passport-style photograph has become a trademark motif of his work. He describes why he has adopted this particular method of representation: "I chose this kind of passport photograph because when you go through customs you are identified by this kind of format. This kind of image represents the person; the personality is very deep and is represented by this small flat photograph".

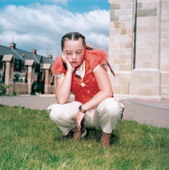

With that said, many photographers endeavour to explore people's individualities, or a least hint towards them in their portraits. Michelle Sank has work across the world, photographing young people. In her series Teenagers, Belfast, she explores ideas about the identity of her sitters. In collaboration with her subjects, Sank negotiated where they would like to have their portrait taken and allowed them to pose exactly how they wished. The various resulting environments reveal something about what is important to the subject yet, perhaps because they always appear slightly out of focus, do not distract the viewer from the sitter.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Teenagers, Belfast

by Michelle Sank |

|

|

|

|

Group Discussion Topics:

- List the different contexts of the photographic portrait, and discuss their varying uses.

- How can a portrait become more of a collaborative act between the sitter and photographer, and how might this improve a portrait of them?

- Ask students how they feel about having their portrait taken. How would they like a photographer to behave towards them?

- Discuss the practical as well as legal issues facing photographing children. What could be the benefits of working with children?

Activities:

- To build confidence in photographing strangers, students should photograph an appropriate number of different people who they do not already know within a given time. They must ask for the subject's consent. Students may work in pairs is appropriate.

- Students should make one or a series of portraits of people in a location that reveals something about an aspect of their character. The subject(s) may be someone they are acquainted with.

- Students should plan and make a self-portrait. They should choose the location and props they would like to use to define their identity and/or their personalities.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|